Sincere Global - International News & Lifestyle

The Condition of the Remaining Cancer Center in Operation in Yemen, May 12, 2017

Every month over 600 come to the only up and running oncology center Al-Jumhuri in Yemen located in Sana’a, seeking treatment. The staggering number of patients has been on the rise since the start of the conflict between the in-country armed parties and external Saudi-led coalition forces. On January 16, 2017, the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs stated that as a low estimate over 10,000 civilians had been killed since the start of the civil war. The war has triggered an economic collapse forcing Yemeni health staff to work without pay and undercutting patients' ability to afford their own treatment which eventually lead a lot of the patients to quit their treatment as their families couldn’t afford medication, transportation and all other related accommodations.

International - Africa

Which way for the Somali refugees under Donald Trump’s administration?

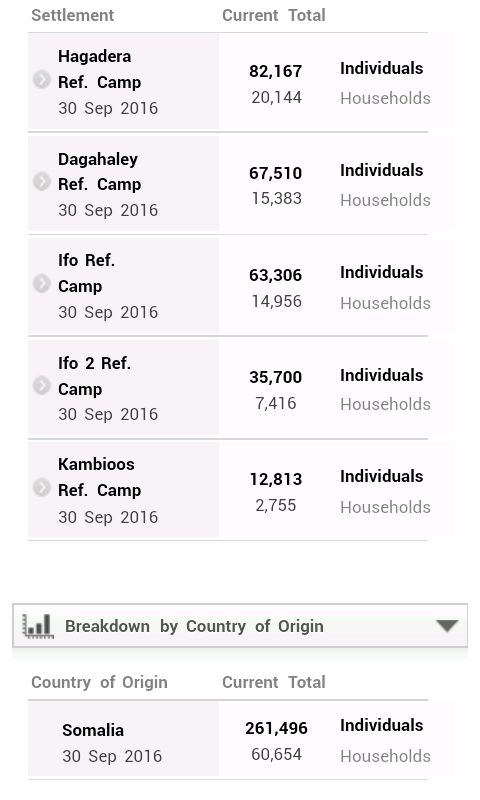

Somali Refugee Population in Dadaab Camps

by Nicholas Mungai - Correspondent (Nairobi), December 8, 2016

“Personally I believe any chance we had to be resettled in the US has faded away with the dust. My personal message to [the President Elect Donald John] Trump would have been to reconsider his stand on the Somalis since we are peace loving community not extremist and violent people. We deserve a chance to be resettled and live in peace.” This is what Abdiaziz Hirsi from the Hagadera Camp in the Dadaab Refugee complex located in North Eastern Kenya said when I sought to know how refugees in the camp had received the outcome of the November 2016 US elections.

Just like many refugees in Dadaab, Hirsi has anxiously been waiting for an opportunity to be relocated to the United States of America. “The main reason I am here in the camp is to wait for my chance to be resettled just like most of my friends who were lucky to have been resettled in the US.” Hirsi who has been in the refugee camp since 1993 believes, “America is the land of dreams and endless possibilities” and reveals to me that he dreams of it every day. Hirsi’s family fast settled at Utango Camp – one of the two initial camps of the Dadaab Refugee Complex before their relocation to the Hagadera camp where he went through Primary and Secondary education. Utango and Marafo camps were established in 1992 to host refugees who were fleeing civil war in Somalia.

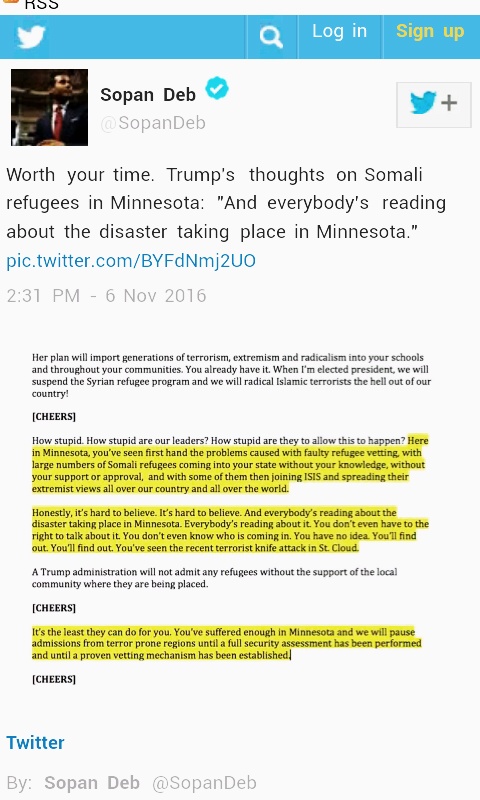

In the November 2016 US election, Republican Party presidential nominee Donald Trump defeated his rival Secretary Hillary Clinton of the Democratic Party contrary to the expectations of many across the world, and polling within the United States. In the final hours of his campaign, the President elect stopped over at Minneapolis – St Paul Airport where in his widely criticized speech warned, “A Trump will not admit any refugees without the support of the local community where they are being placed.” He decried the suffering the people of Minnesota had been subjected to by terrorism allegedly from unscreened refugees. “Why, just yesterday we allowed entry of a known refugee from the truth who keeps threatening American citizens with death, disasters, and a trip to hell?”

Twitter posting on Trump's speech in Minnesota

Abdiaziz Hirsi says that his dream and that of his family for a better life in the US was very much alive until the news of Donald Trump’s win found its way into the refugee camp. He is also of the opinion that situation is further complicated by the perception that the camp is a security threat to Kenya. “Yes, we have waited for too long, I was very optimistic that soon rather than later I and my family members will get their chance to be resettled but unfortunately Mr Trump’s win and Kenya's unfounded accusations of the camps have complicated everything and created a pool of pessimism and disappointment everywhere, unless president Trump reconsider his campaign promises concerning the Somalis and Muslims in general.”

Abdirahman of the Dadaab Voices, a social media platform by young refugees in the camp is skeptical if the Trump Administration will continue the plans that the President Obama administration had put in place for the resettlement of Somali refugees. We don’t foresee Obama’s promise fulfilled under Trump leadership. He had said his administration is doubling the number of refugees being resettled. Trump will be sworn in on 20th January 2017, which means he will be responsible and will be in control of all foreign and domestic policies. Our main worry is if Trump fulfils all his campaign policies on refugees, Muslims and other minority groups.”

That Donald Trump led a campaign that appeared to pit him against minority groups, Muslims and refugees, is a fact stuck in Adirahman’s mind. He is alert to reports that during his campaign visit to Minnesota, the President elect asked for a thorough vetting of refugees and asylum seekers entering America. He holds the opinion that Donald Trump might have anchored his position about the vetting of refugees on a wrong understanding of the refugees vetting process. “He [Trump] doesn’t know much about the resettlement process and what it takes; refugees go through numerous vetting, check-ups including their background. Refugees also wait to be resettled on average for three to four years from the first time the UNHCR interviews a family or an individual.”

A report on CNSNews.com by Patrick Goodenough says about 100000 Somali refugees have been resettled in the United States since 9/11, with the largest number of this number living in Minnesota. The current financial year has seen over 8000 Somali refugees. 99.6% of the total number of refugees admitted to the US since 2001 is Muslim.

Comments

Repatriation Cloud Over World’s Largest Refugee Settlement Darkens as Closure Deadline Nears

Brownkey Abdullahi (Right) with Nobel Laurette Malala Yousafzai (Left) – Malala spent her 19th birthday in Kenya’s Dadaab camp in her bid to draw the attention to the global migrant crisis and the plight of those living in the camp.

by Nicholas Mungai - Correspondent (Nairobi), Nov 14, 2016

How the Government of Kenya will close of the world’s largest refugee camp by end of November, 2016 becomes more visible, a cloud of uncertainty for the refugees at Dadaab refugee camp continues to darken, with the fast approaching deadline.

Some refugees who have lived in the camp for nearly a quarter century have expressed concerns over the imminent repatriation with some vowing never to return to Somalia.

The voices of refugees in the Dadaab camp have, according to the ‘Dadaab voices’ Facebook page, not been prominently captured in the previous repatriation processes. A November, 6, 2016 post on a ‘Dadaab voices’ says, “…There were so many errors in the build up to the Tripatite Agreement.” According to the administrators, Dadaab Voices is a social media platform created to enhance connection between refugees in the Dadaab and those living outside, telling the camp’s belief that representatives from the camp were not invited to express their concerns that the Somalia government did not clarify if it was capable of receiving and providing the voluntary returnees with the necessary support.

In what is seen as a move to consider the voices of refugees ahead of the 30th November 2016 deadline, representatives from a national Multi-agency Repatriation Team on October, 31 met with the Dadaab refugee leaders at a consultative gathering which gave refugees an opportunity to air their concerns and fears over the impending closure of the Dadaab refugee camp. The refugees highlighted the looming famine and drought in Somalia, a recent upsurge of inter-clan clashes, political uncertainty occasioned by the 2016 election campaigns, and the worrying trend of refugees who had earlier opted to voluntarily go back to Somalia but have been returning to the Dadaad camp, as some of the reasons which are making the refugee community hesitant to return to Somalia.

A video conference featuring the local refugee leaders and representatives from various European countries and the United States of America, held at the end of October 2016 acknowledged that the Dadaab camp has been off the donor support radar. The US representative revealed during the meeting that the USA has increased slots for the Kenya refugees in the 2016 fiscal year to 7000 and will be increasing the number to 9000 in 2017. The UK pledged to extend their support to returnees in Somalia.

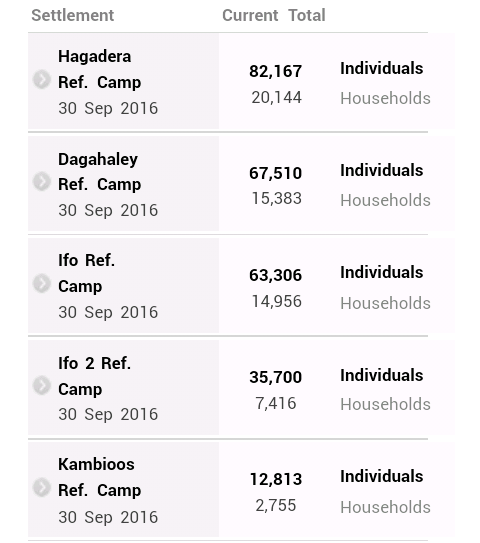

Somali Refugee Population in Dadaab Camps

To find out how the announcement by the Government of Kenya, in May 2016, on the closure of the Dadaab camp has effected the lives of refugee living there and the neighboring host community, I recently held a conversation with Brownkey Abdullahi. According to Abdullah, a young female rights activist and the first Dadaab female blogger who has lived in the camp for over 20 years, said “the repatriation has had greater influence in the economics of the refugees and it is a forced repatriation since the government clearly announced the closure of the Dadaab camps.”

According Abdullahi, “the host community has interacted with the refugees very well and the interaction has been a major boost to the locals, but this is very likely to change once the camps are closed. The future is in fact bleak for people who have invested in the camps over the years and incidents of insecurity triggered by impending closure, …people think they will end up nowhere if the refugees leave. Among the refugees themselves due to force of the government, they have harboured grudges and they started evil behaviors.”

Brownkey Abdullahi interacts with families in her quest to advocate for the rights of the refugee girls. She observes that the current exercise has affected education, interfered with families and in some led to family breakups. The situation is further complicated by lack of information on the repatriation process by the UNHCR. Abdullahi continued, “It’s only the Kenyan government officials who actively talk to the refugees about the ‘voluntary return’. Apparently, in the camps, the ‘voluntary repatriation is seen as a cover book to close the Dadaab camps…”

Brownkey Abdullahi_Dadaab Refugee Camp Female Activist & Blogger

Refugees in the five camps of the vast refugee settlement believe that whatever is happening today clearly signals the end of their time in Dadaab. In July 2015 food rations to the camps went down by 30% and other humanitarian aid has visibly been on the decline. Abdullahi is worried that the May 2016 directive to close Dadaab has adversely affected the refugee communities and humanitarian service providers, “UNHCR and other NGOs’ programs and priorities are affected. Business people do not lend credit to their fellow refugees, students are adamant to go to school and many humanitarian organisations have echoed their funding shortfall as there has been shortage of water in the camps.”

Although the refugees are fearful of going back to “a no-go-zone” they are left with very limited options. Some have their bags already packed because of the looming November deadline for the closure of the camp. This is happening even after some of those who had already voluntarily returned under the 2013 Tripartite voluntary repatriation program found it difficult to live in Somalia. “Already thousands who returned to Somalia through the Voluntary Repatriation have again turned back to the camps. …some women suffered rape and children lost their parents,” said Abdullahi as we concluded our conversation.

Two civil society organizations: Kenya National Commission on Human Rights (KNHCR) and Kituo Cha Sheria have already filed a petition in the Kenya courts of Law seeking to challenge the constitutionality of the Government’s decision to close the Dadaab refugee camps and disband the Department of Refugee Affairs (DRA). Civil society organizations opposed to the camp’s closure believe that that it would be a disastrous to send refugees back to a country where the conditions that forced them to seek refuge in Kenya are yet to improve and that by doing so Kenyan authorities would be failing on their international commitment to the protection of refugees.

Kenya Refugee Crisis: Report urges for return to the Tripartite Agreement on repatriation of Somali Refugees

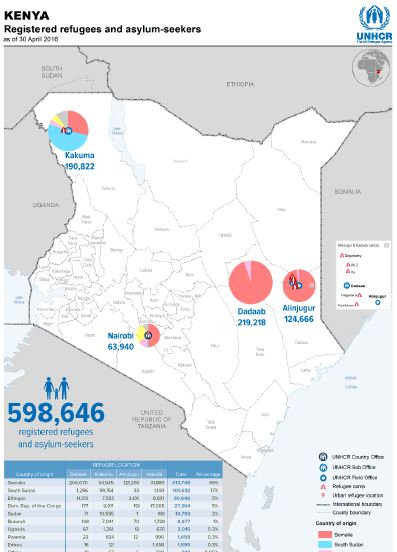

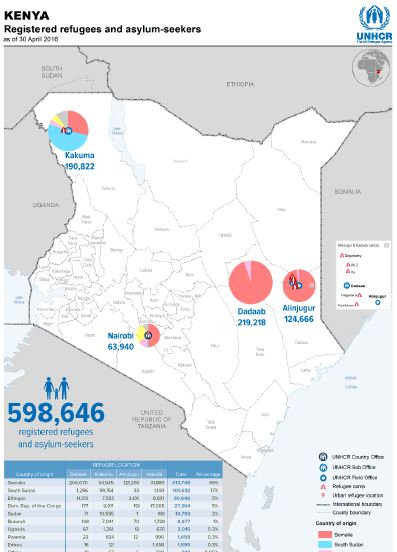

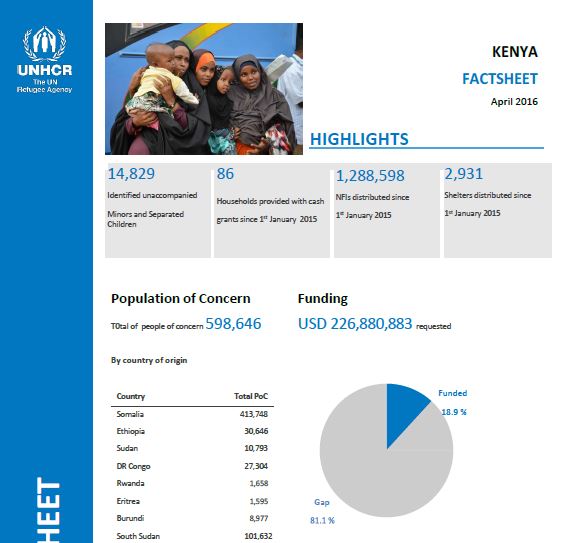

UNHCR Fact Sheet on Number of Refugees in Camps in Kenya

by Nicholas Mungai - Correspondent (Nairobi), October 22, 2016

The Norwegian Refugee Council in Kenya (NRC) has in a Position Paper published in October 2016 said the current exercise to repatriate Somali refugees fails to meet international standards for voluntary returns and recommended to the governments of Kenya and Somalia to return to the much organized and planned repatriation process as per the 2013 Tripartite Agreement.

The report also calls for suspension of the deadline imposed by the Government of Kenya for the closure of the Dadaab refugee camps by November, 2016. The report which is titled ‘Dadaab’s broken promise’ and fore-worded by NRC’s Secretary General Jan England was released to the public on 10, October argues that refugees in the camps remain in need of international protection.

In his foreword, Jan England notes, “…the pressure to push out more than 280,000 registered refugees from the camps has led to chaotic and disorganized returns. Many Somali refugees feel trapped following the Kenya government’s decision to close the camps by the end of November.”

England says the sudden announcement on May, 6, by the Government of Kenya to close the largest refugee camp in Kenya, broke the promise of the initial returns program under the 2013 Tripartite Agreement, and that action to reinstate voluntary, safe and dignified returns as well as protection for the Dadaab refugee community should be prioritized.

“The Kenyan government and the UN refugee Agency (UNHCR) should reinstate the organized process of return under the Tripartite Agreement. The unrealistic deadline must be removed before the situation further deteriorates.” Jan England. According the NRC official, repatriations under the initial agreement was largely a success considering that refugees who volunteered to return to Somalia would be assisted to reach their return locations in safety and dignity.

Disbandment of the Department of Refugee Affairs (DRA) and the subsequent creation of its successor – the Refugee Affairs Secretariat and a Multi-agency Refugee Repatriation Team which are yet to be anchored in Kenyan law have also been blamed for slowing down the returns from the Dadaab refugee camp to Somalia.

The Norwegian Refugee Council’s report observes that following the decision to restructure the management of refugee affairs by the government of Kenya, reports of “intimidation and coercion of refugees” to return to Somalia have been received, registration of new refugee arrivals suspended and coordination structures in refugee camps undermined. “Humanitarian assistance, and UN and NGO resilience projects in the camps now face greater barriers to being implemented” adds the report.

The Norwegian Refugee Council has identified three issues which they believe are going to set up the repatriation process under the November deadline for failure. According to their report, the repatriation under the current context is not voluntary, mechanisms being put in place to ensure the protection of returning refugees are not strong enough and the process is just creating a revolving situation.

The 8-page report notes that the situation is complicated further by lack of matching resources available to facilitate post arrival humanitarian assistance, the pressure to speed up the repatriation process which has led to much focus on modalities of return instead of also considering the sustainability of the returns. Sustainable returns will prevent returnees from ending up in internally displaced camps or returning to Kenya as undocumented refugees.

It warns that if not managed properly the return of refugees to Somalia is likely to trigger internal conflict between the returnees and host communities due to increased pressure to the already insufficient existing services, such as health, water and education. NRC says interventions should be focused on enhancing self-sufficiency adding, “The needs of refugees are most acute immediately after arrival, but also grow over time, as return packages become exhausted and livelihood opportunities are exhausted.”

Authorities in lower State of Jubaland – an autonomous region in southern Somalia, are reported to have blocked over 1000 returnees arriving in Dhobley from further travel, as they suspended returns to Jubaland until donor funding promised for basic social services is met. Jubaland authorities have also expressed concern that “largely unplanned” nature of returns could threaten an already volatile security situation.

The Norwegian Refugee Consortium is appealing to the United Nations and Non-Governmental Organizations to readjust programs in Kenya and Somalia to incorporate the three tier approach to returns: repatriation, reintegration and resilience, and at the same time scale up local level coordination in areas of returns supporting the government of Somalia to meet returnees needs through a resilience lens. They have also implored the donor community to commit and provide reintegration and development programming funding, and technical support to the Government of Somalia and local authorities to manage the return process.

Closure of Largest Refugee Camp Dabaad in Kenya Very Imminent

UNHCR Fact Sheet on Number of Refugees in Camps in Kenya

by Nicholas Mungai - Correspondent (Nairobi), June 23, 2016

A heavy repatriation cloud hangs over the largest refugee camp in East Africa (Dadaab) as the debate on whether or not Somali refugees in the camp should be sent back continues in Kenyan government. On 6th May 2016, Kenya amplified its resolve to send back over 300 000 refugees back to Somalia when it announced the plan to shut down the Dadaab refugee camp.

In the announcement, Kenya backed the move for a speedy reparation exercise citing financial constraints, environmental degradation, insecurity and slow implementation of a tripartite voluntary repatriation agreement signed in November 2013 with UNHCR and the Government of Somalia. The Tripartite Agreement expires in November 2016, and according to the Kenya government “a decision has to be made to beat the deadline.”

A government department that was mandated to deal with refugee affairs has already been disbanded and a taskforce constituted to oversee the repatriation of over 500,000 refugees expedited.

The decision has attracted mixed reactions from the international community, human rights bodies and local civil societies.

Refugee Consortium of Kenya (RCK) is among organizations that have reacted to the announcement by the Interior Ministry’s Principal Secretary, Dr. Karanja Kibicho, on 6th May 2016. The organization works with, and for forced migrants including: refugees; asylum seekers, Internally displaced persons and victims of human trafficking.

RCK’s Communication, Research and Monitoring Project Officer Andrew Maina believes that “legally some provisions were more or less breached” by the government.

Some refugees have spontaneously, and voluntarily been returning to Somalia under the November 2013 Tripartite Agreement on repatriation between Kenya, UNHCR and the Somalia Government, but the government wants a speedy process, and has maintained that it will not accept compulsion to solve its national responsibilities to accommodate international obligations at the expense of the country’s citizens.

A UNHCR report depicting a weekly update and support to voluntary repatriation of Somali refugees from Kenya states that a total of 7,157 refugees have in the period: of January 2016 to May 8, 2016 voluntarily returned to Somalia.

RCK says the government should be patient because the most recent trend depicts an increase in the number of refugees returning to Somalia. Number of arrivals from Kenya between January and early May 2016 surpassed the December 2014 - December 2015.

According to RCK, “Repatriation process is voluntary and everything that is voluntary or requires some form of human-will would take time. People who have been here for 25 years + convincing them to go back home would not take a day at times it may even take 10 years. We still have Rwandan refugees here from 1994, this is 2016, that has been more than 20 years, that conflict ended long time ago but they still do not feel safe to go back.”

The government of Kenya has however maintained her persistence that Somali refugees have to return to Somalia.

Kenya’s Deputy President William Ruto, in an address to World Humanitarian Summit in Turkey asserted that the decision to close Dadaab was final as he refuted claims that Kenya’s decision to close the Dadaab refugee camps was a ploy to seek for more funding from donors.

President Uhuru Kenyatta was in Brussels, Belgium in early June, 2016 where he also held a meeting with the UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon. The meeting, according a local daily in Kenya quoting the country’s Foreign Affairs Cabinet Secretary, Ambassador Amina Mohamed was “basically to bring Ban up to speed on the matter."

Before end of June, 2016 a high-ranking UN official is expected in Nairobi for a follow-up meeting to Kenyan President Kenyatta and UN Secretary General Ban Ki-Moon. The Nairobi meeting will discuss the matter further and it is widely expected to come up timetables for repatriation as well as a safe destination in Somalia where the refugees could be resettled.

In what is interpreted as UN’s support to Kenya’s resolve to send back home Somali refugees, a forecast is already in the air as reported by Kenya’s Standard Digital that Kenya will be taking the discussion on this humanitarian issue to the next level during the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD).

The 14th session of the UNCTAD , whose theme is “From Decisions to Actions”, will take place from July 17-22, 2016 and it is on the sidelines of the event that Kenya expects to discuss further the modalities of the repatriation of Somali refugees with the UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon.

The Somali refugee population in Kenya is currently 413,748 individuals with 111,045 households as of April 30, 2016. Of this population, 206,070 are in the Dadaab camp (in Northern Kenya), 54,545 in Kakuma camp (North Western Kenya), 121,250 in Alinjugur, and 32,688 individual in Kenya’s capital, Nairobi as urban refugees.

UNHCR Fact Sheet on Refugess in Kenya

Other countries currently with refugees in Kenya are: Ethiopia (30, 646); Sudan (10793); The Democratic Republic of Congo (27, 304); Rwanda (1,658); Eritrea (1,595); Burundi (8,977) and Uganda (2,010).

Kenya Begins Process to Expel 600,000 from Refugee Camps

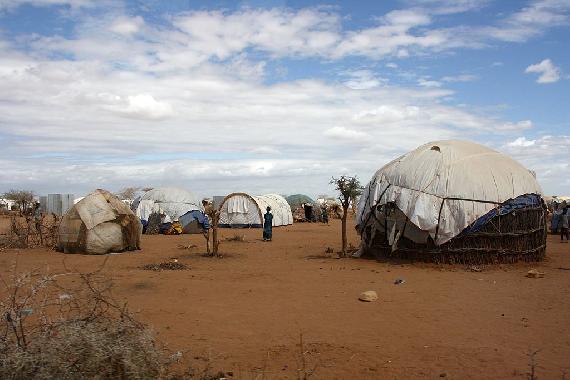

Refugee shelters in the Dadaab camp complex, made with plastic sheeting, July 16, 2011 (CC BY 2.0 UK Department for International Development)

by Nicholas Mungai - Correspondent (Nairobi), May 7, 2016

The government of President Uhuru Kenyatta of Kenya has initiated a process for repatriation and eventual closure of refugee camps in the country citing very heavy economic, security challenges such as the threat of Al-Shabaab and other related terror groups that hosting of refugees has continued to pose to Kenya, environmental burdens and the slow nature of repatriation.

In a move that has already been termed as a serious indication that Kenya is determined to close refugee camps, on May 6, 2016 the interior ministry’s Principal Secretary, Dr. Karanja Kibicho released a statement announcing that the Government of the Republic of Kenya has decided that hosting of refugees has to come to an end.

“In this regard, the Government of Kenya has disbanded the Department of Refugee Affairs (DRA) as a first step. Further, the Government is working on mechanism for closure of the two refugee camps within the shortest time possible", according to the Principal Secretary's statement.

The Kenyan Government in acknowledging that the decision might have adverse effects on the lives of refugees has invited the international community to collectively take responsibility on the humanitarian needs that will arise out of this action, and support the initiative so that the process to shut down the two camps can be expedited.

Kenya is home to over 600,000 refugees in the Dadaab and Kakuma camps for nearly 25 years. The majority of the refugees and asylum seekers in the two camps are from neighboring countries: Somalia, South Sudan and Ethiopia. They have fled civil war and general insecurity in their respective countries.

In November 2013 a tripartite agreement was signed to govern and lay ground for voluntary repatriation of refugees to Somalia and eventual closure of refugee camps. The statement from Kenya’s government says the subject of repatriation and the closure has been discussed in many forums including the UN, African Union and the East African Region.

The Department of Refugee Affairs in Kenya manages refugee affairs and coordinates maintenance services. This department derives its mandate from the Refugee Act, 2006 and the 2009 Registration regulations. Kenya is a signatory to the 1951 Geneva Convention which relates to the protection of refugees, the 1967 protocol as well as the 1969 Organization of African Union (OAU) convention.

Away from Home: How South Sudanese Refugees in Kenya Cope

Entrance to Kakuma Camp (Photographer: Nicholas Mungai)

by Nicholas Mungai - Correspondent (Nairobi), August 10, 2015

On 9th July 2015, South Sudan celebrated the country’s fourth independence anniversary. The anniversary marked the East Africa nation’s four years of self-rule, following its independence declaration in 2011. A successful secession referendum vote on 9th January 2011 preceded the birth of the newest nation in the world.

A peace process spearheaded by the Intergovernmental Governmental Authority on Development (IGAD - an eight-country trade block in Africa) culminated in a Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) signed on 9th January 2005, bringing to an end one of the longest civil wars.

Guided by a vision of a secular and democratic Sudan, the South, under the leadership of the Sudanese Peoples Liberation Movement’s (SPLM) military wing (SPLM/SPLA), waged a civil war in 1983 against the government for 22 years. The war left over a million dead and forced thousands to flee their homes for safety in neighbouring countries.

Many South Sudanese returned to their country after independence in 2011. Some remained in camps or in residential homes in neighbouring countries where they had been forced to seek asylum, as they monitor the peace situation, away from home.

Independent South Sudan continues to face instability and there are currently ongoing internal violent conflicts. A deadly violent conflict triggered by a political struggle between President Salva Kiir and his former deputy, turned political rival, Dr. Riek Machar erupted on 15th December 2013.

This renewed conflict has resulted in deaths of an estimated 10,000 people, according to a report by the International Crisis Group, and displacement of more than 1.5 million civilians. Those fleeing the internal conflict have been subjected for a second time to a life in refugee camps in the neighbouring countries of Ethiopia, Kenya, and Uganda. The civil war has also disheartened the hope of many South Sudanese who have been considering returning home after the second civil war.

The government of Kenya in conjunction with UNHCR manages Kakuma refugee camp in Kenya. Created in 1992, the camp today accommodates 180,000 refugees from Ethiopia, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Rwanda, Burundi, South Sudan and Somalia.

The population of South Sudanese refugees in Kakuma camp, according to UNHCR records was estimated, at 91,554 by July 2015, doubled from 45,239 in 2013. There are approximately 9,884 households. As of January 2013, the UNHCR registered 56,000 asylum seekers and refugees outside of the camp in Nairobi and other urban centres in Kenya.

Sarah Abuk, a 21 year old South Sudanese refugee, lives in Nairobi’s urbanized centre of Eastland, where a substantial number of South Sudanese reside outside of the camp. She had lived in the vast Kakuma refugee camp for close to a year, before her parents were able to have her and other family members relocate to the city in 2006.

Life in Kakuma camp was not that easy for Abuk, who had been rescued in 2004, from intense fighting in Yirol, central South Sudan. Yirol was a key target for bombings by the North, as well having been engulfed by inter-clan violent conflicts.

“Life in Kakuma actually was not so easy. Regarding education, we were not that much focused. The teachers were not qualified. Most of us went to school to enjoy Uji [porridge]”, said Abuk when we caught up with her in their family’s rented house in Nairobi for an interview.

Sara Abuk at home

Security is always a concern for refugees in camps, considering that individuals from different social contexts and security backgrounds inhabit the camps. To Sarah Abuk, Kakuma refugee camp is not an exception. They were forced to make local arrangements to secure the little they had in their makeshift houses. Strong young men were assigned the security duty to supplement the general security provided by the host’s security team.

Ethnic differences among South Sudanese in Kakuma refugee camp have always contributed to insecurity. In 2014, an alleged rape incident, which left a 9-year-old girl unconscious, sparked a violent fight between two communities within the camp. Scores were injured and others killed.

Food supplies to refugees in the camp is said to be insufficient. Sarah Abuk described to us that relief rations distributed by humanitarian organizations were not sufficient to meet the refugees’ hunger needs. There were days they would have to put up with a cup of porridge. Tough times pushed some refugees to sell the food rations to purchase other personal effects. The food would find its way to the two markets (Hong Kong and Habesh) which are located in the camp.

Thirst for money, an indicator of poverty among refugees in the camp, came to fore recently when the sources within the camp we had identified to interview for this article reversed their decision to grant us an interview. According to our go-between in Kakuma - a South Sudanese journalism student at a Nairobi university, the contacts could have potentially changed mind in anticipation for a kickback.

Urban refugee’s journey for life in Kenya’s capital usually begins with a tiresome long drive to Nairobi by bus. Sarah Abuk explained that supervision was not very tight at the camp. This made it easy for refugees to leave the camp at night for Nairobi. Those without proper travel and migration documents had to part with a bribe to have their way past police checkpoints along the way.

The motivation by refugees to venture into the city life emanates from the desire for quality education and better city life. It is also much easier for refugees to obtain travel documents to other parts of the world from Nairobi.

In urban areas, South Sudanese contend with the challenge of accessing affordable housing, education, and fair treatment in city markets. They live in over-crowded houses exposing them to higher infection rates for communicable diseases and discrimination by residential house owners.

Sara Abuk at home

Sara Abuk at home

“We were many. Others used to sleep on the floor, others in the sitting room. Most of the South Sudanese in Nairobi are always many in one house. Nowadays even the property owners do not accept South Sudanese because they live in large numbers in a three-bedroom house. What they think of is that they are just coming to destroy their houses,” said Sara Abuk.

Abuk lives with 15 family members in a rented house. She explains that South Sudanese come from extended families, and it is part of their tradition to live in a community, “If you are one family, there is no need of living separately. We stay together, eat together, share life and are happy together”

The perception among many Kenyans that South Sudanese refugees have a lot of money, presumably from stipends received for the United Nations, renders urban refugees like Abuk vulnerable to exploitative prices of commodities in city markets. House owners also hike house rents upon discovering that a family is South Sudanese.

Abuk dismisses the claim that refugees receive money from UN agencies pointing out that it is through struggle that they raise money for their basic needs including; housing, feeding, education and clothing.

“Mostly when you go buying they just see a South Sudanese. They tell themselves that this person has money so they increase the prices. It was just the day before yesterday I had gone out to look for a house. I saw a woman who was moving out. I asked her the price and she said she was paying $400 USD. When I called the proprietor, first she asked my name, I also said I am a South Sudanese. She just increased the rent $600 USD.”

At one point in 2010, Sara Abuk and her siblings could not be admitted to a school in the outskirts of Nairobi. It was difficult for her parents back in South Sudan to meet the high cost of school fees for over 22 children. This forced them to stay out of school for almost a year before securing a discounted school fee rate at a school in Eastland, Nairobi.

In her parting thoughts, Sara emphasized that people should be treated equally regardless of their countries of origin, colour or status. She also expressed disappointment with the prevailing violent conflict in post independent South Sudan, adding that it was discouraging to see South Sudanese return to refugee camps instead of staying in their country peacefully.

Copyright(c) 2015-16, Sincere.Global